ISABEL RUBIO ARROYO | Tungsteno

Winter temperatures in Antarctica are low enough to freeze water all the time, according to NASA. This ice-covered continent "is too cold for people to live there for a long time." While the aim in the 20th century was to build practical bases that could house scientists, today architects are also prioritising other objectives that take this discipline into unprecedented territory.

Scientific bases in the planet’s coldest corner

The Antarctic Treaty, signed in Washington on 1 December 1959, set aside this continent for scientific research. Scientists take turns visiting and conducting research to, for example, better understand climate change, ozone depletion and sea level rise. "The Antarctic region is a matchless 'natural laboratory' for vital scientific research that is important in its own right and impossible to achieve elsewhere on the planet," says the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR).

Scientists are housed in research bases that are prepared for the extreme cold and have become more efficient and aesthetically pleasing in recent years. "As architects, we are concerned with human comfort, so we set out to create a kind of atmosphere that would promote well-being," Emerson Vidigal, a principal at Estudio 41, the Brazilian architecture firm that designed the Comandante Ferraz Research Station, told The New York Times.

Some architects prioritise aesthetics and energy efficiency in state-of-the-art scientific research stations. Credit: Estudio 41.

Increasingly aesthetic and sustainable buildings

Brazil's Comandante Ferraz Research Station was praised by The New York Times as something that "could be mistaken for an art museum or a boutique hotel." It was designed by the architects of Estudio 41, after its predecessor was destroyed in 2012 after an explosion in the machine room ignited a fire. Its creators claim that in certain places on the planet, "thinking about a building is almost like constructing a garment, an artefact that protects and comforts."

"This is a problem of technological performance, but one that must be combined with aesthetics," they say. The structure is made up of several blocks: an upper one that houses the cabins and the dining/living area, a lower one that includes laboratories and areas for operation and maintenance, and a transverse block that houses a video room/auditorium, a meeting/videoconferencing room, a library and a lounge. The station also has photovoltaic panels and wind turbines.

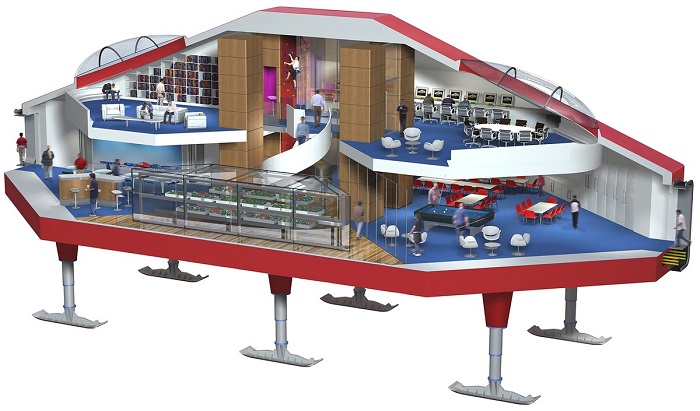

Some Antarctic structures have also been given an attractive design and a futuristic feel. The Halley VI British Antarctic Research Station is mounted on giant steel skis and hydraulically powered legs that allow the station to "climb" and rise above the snow each year and to be moved. It consists of several blue modules that house sleeping quarters, laboratories, office areas and energy centres inside. A larger, two-storey red module is, in the words of its designers, the social heart of the station and is used for living, dining and entertainment. "Inspiring interior design provides an uplifting environment to sustain the crew through the long, dark winters, helping to combat the debilitating influence of Seasonal Affective Disorder (a type of depression that comes and goes with the seasons)," says Hugh Broughton Architects, the design firm.

The red module at the Halley VI Research Station is intended for dining and entertaining. Credit: Hugh Broughton Architects

While some architects design new structures, others work to modernise existing ones. An example of this is McMurdo Station, operated by the United States and the largest in Antarctica, which began in 1956 as a temporary naval base and has grown in an ad hoc manner to encompass more than 100 buildings. The Antarctic Infrastructure Modernization for Science (AIMS) project aims to improve energy efficiency and reduce operation and maintenance costs at McMurdo Station. This is vitally important, according to Alexandra Isern, head of Antarctic sciences at the National Science Foundation, because "the more we spend to keep the building going, the fewer resources we have to get researchers out in the field."

The challenges of building in Antarctica

To construct these types of bases, there are a number of challenges to overcome. Christopher Robert Lloyd, a site supervisor for the Danish architecture and engineering firm Ramboll and currently working on a new Antarctic scientific support facility at the British-operated Rothera Research Station, explains that "there’s really no such thing as a ‘standard’ polar laboratory to copy from, and the building must incorporate an aircraft control tower, a snowplough and skidoo garage, and facilities to make fresh water and electricity for the entire station. There aren’t many buildings in the world that can do that, or anything similar."

Furthermore, the station has to be completely self-sufficient and able to adapt to any need: "A field workshop may have to double as a dining room one year or, if the worst comes to the worst, a field hospital in another," says Lloyd. In addition, it is not easy to build in Antarctica using materials found in the environment. In a place with no trees or bushes there is no wood, so almost all bases are built using prefabricated elements that are assembled on site.

The scientific bases are mainly built with prefabricated elements and aim to be self-sufficient. Credit: Estudio 41

Architects have sought to overcome all these challenges and build in a unique environment. Bert Buecking, a partner at bof architekten, tells The New York Times that a radical change in the approach to these projects came about relatively quickly. "When the UK built Halley VI, many nations realised the importance of doing something special, and not just doing something," he concludes.

· — —

Tungsteno is a journalism laboratory to scan the essence of innovation. Devised by Materia Publicaciones Científicas for Sacyr’s blog.