horas de promedio de formación por empleado

Sostenibilidad

Construimos desde hoy un futuro mejor

En Sacyr somos conscientes del rol que tenemos como impulsor del cambio en la sociedad por lo que la sostenibilidad es un pilar fundamental de nuestras actividades.

Enfocamos nuestra visión ASG a aquellas áreas en las que la organización puede generar mayores impactos en los ámbitos ambiental (economía circular, lucha contra el cambio climático, capital natural, agua, ciudades sostenibles), social (personas y comunidades) y de gobernanza (ética y derechos humanos, transparencia, innovación, finanzas sostenibles, gestión de riesgos).

M€ en valor económico distribuido

de residuos reciclados, reutilizados y valorizados

de mujeres en posiciones de liderazgo

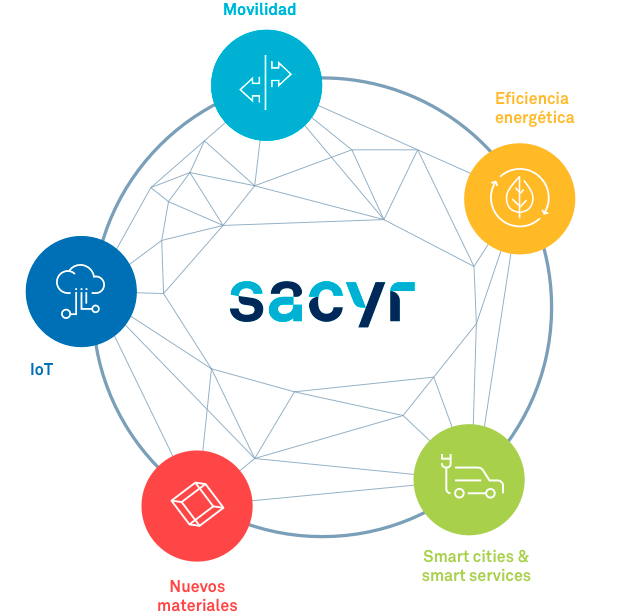

Innovación

Imaginamos soluciones

Damos forma a las ideas. Transformamos nuestro entorno con talento y energía. Fomentamos la cultura de la innovación y trabajamos con un modelo abierto para impulsar el cambio

Desarrolla tu carrera en Sacyr

Las personas son la clave de nuestro éxito. Conoce nuestras coordenadas y súmate a nuestro equipo.