ISABEL RUBIO ARROYO | Tungsteno

De pajitas a cubertería o envases pasando por ropa, electrodomésticos y smartphones. En un planeta invadido por el plástico, la difícil degradación de este material plantea un enorme reto ecológico. Una bolsa puede tardar más de 20 años en descomponerse. Una pajita, más de 200. Y una botella, unos 450. Encontrar plásticos más sostenibles y que no contaminen el planeta es uno de los grandes retos del siglo XXI. De ahí la repercusión internacional del hallazgo de un equipo de científicos chinos: han creado un plástico que se degrada solo en una semana gracias al sol y al aire. Pero, ¿hasta qué punto puede este nuevo material poner fin a este gran desafío medioambiental?

Un plástico que se degrada en un tiempo récord

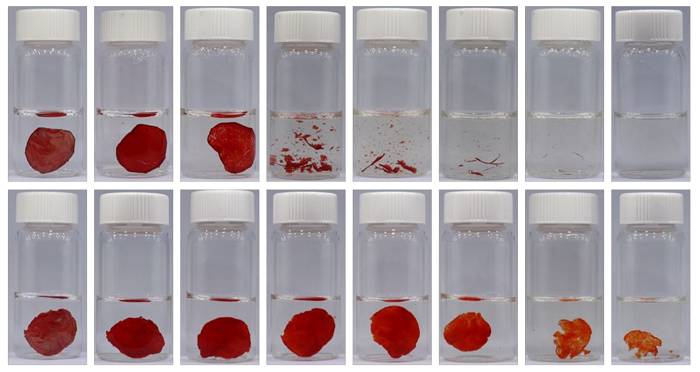

La investigación ha sido publicada en Journal of the American Chemical Society (JACS) y difundida por revistas de alto prestigio como la reputada PNAS. Este polímero es capaz de descomponerse en tan poco tiempo porque la exposición solar cambia su composición molecular. El proceso se produce por la degradación fotooxidativa: la irradiación de la luz del Sol rompe la estructura de carbono de doble y triple enlace del polímero. Durante esta reacción, se forma el ácido succínico, una pequeña molécula de origen natural que no es tóxica y no deja microplásticos en el ambiente.

Conseguir materiales capaces de degradarse rápidamente es importante para salvaguardar el medioambiente. Hay más de cinco billones de piezas de plástico flotando en la superficie del océano. Todas ellas pesan en total unas 268.940 toneladas. O lo que es lo mismo, el peso equivalente a 27 torres Eiffel. Y esto solo representa el 1% de los plásticos de los océanos: el 5% se encuentra en las playas y el 94% se ha hundido en el fondo marino. De todos los plásticos que se vierten al mar, el 80 % proviene de la tierra, según el informe Plásticos en el medio marino de la consultora Eunomia. Antes de degradarse, todos estos plásticos pueden dañar a la fauna marina. Cada año más de un millón de aves y de 100.000 mamíferos marinos mueren como consecuencia de todos los plásticos que llegan a los océanos, según Greenpeace.

Hay más de cinco billones de piezas de plástico en el océano que tardarán entre décadas y cientos de años en degradarse. Crédito: Unsplash.

Un material flexible potencialmente útil en el sector de la electrónica

Pese a que el hallazgo de este equipo de científicos chinos suena prometedor, este plástico todavía está en proceso de investigación. Liang Luo, coautor del estudio y científico de materiales orgánicos de la Universidad de Ciencia y Tecnología de Huazhong en Wuhan (China), calcula que aún podrían pasar entre cinco y 10 años hasta su comercialización. Además, este polímero no resultaría útil en todos los sectores. Luo no considera una buena opción utilizarlo para crear botellas o bolsas de plástico que necesitan durar más de una semana en las tiendas.

En cambio, este material flexible y degradable podría ser utilizado en el campo de la electrónica. Por ejemplo, para fabricar smartphones y otros dispositivos electrónicos flexibles. En estos casos, al no tener contacto con la luz ni con el oxígeno, el material podría durar años y después “haría que los smartphones pudieran desecharse más fácilmente al final de su vida útil”. El ácido succínico resultante podría además reciclarse para ser utilizado en las industrias farmacéutica y alimentaria, según el experto.

El químico de materiales Zhibin Guan, de la Universidad de California, considera que esta investigación es "un ejemplo emocionante de polímeros conjugados degradables". Pese a que reconoce que este plástico podría ser útil en el sector de la electrónica, advierte: “Se necesita más trabajo para demostrar la generalidad de este mecanismo”. Para el químico de polímeros Eugene Chen, de la Universidad Estatal de Colorado, este es un ejemplo de una "degradación casi ideal del plástico". El experto está convencido de que usar la luz solar y el oxígeno para descomponer el plástico en lugar de centrarse en la actividad microbiana es un gran avance.

Un equipo de científicos ha creado un plástico que se degrada solo en una semana gracias al sol y al aire. Crédito: Journal of the American Chemical Society.

La huella ecológica de algunos plásticos biodegradables

Existen diferentes compañías e investigadores de todo el mundo que tratan de crear plásticos capaces de descomponerse en determinadas condiciones, por ejemplo, de temperatura y humedad, y distintos periodos de tiempo. En España, un proyecto encabezado por el Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC) ha logrado elaborar un envase biodegradable a partir de suero de queso y microcelulosa de cáscaras de almendras. En teoría este material puede alargar la vida útil de carnes, pescados o verduras y desintegrarse en un periodo máximo de 90 días tras ser desechado.

Otro equipo de investigadores, de la Universidad de Yale, ha creado un plástico biodegradable a partir de polvo de madera que se descompone en tres meses. En este caso, podría utilizarse para crear bolsas, envases e incluso en el sector de la construcción y el automovilístico. Pese a todas estas iniciativas prometedoras, aún queda un largo camino por recorrer. La Agencia Europea de Medio Ambiente indica que en la actualidad solo el 1% de los plásticos y productos plásticos en el mercado global se consideran de base biológica, compostables o biodegradables.

Además, los plásticos que algunas compañías definen como biodegradables también tienen su propia huella ecológica. “La mayoría de los plásticos se siguen fabricando a partir de combustibles fósiles en un proceso que contribuye al aumento de las emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero a lo largo de su cadena de valor”, afirma la agencia. De hecho, muchos plásticos contaminan en todo su ciclo de vida: desde la producción hasta el uso y, finalmente, a través de su eliminación.

Gran parte de los polímeros que utilizamos en el día a día permanecerán decenas de años en vertederos, el mar e incluso la atmósfera. Un estudio publicado en Science Advances alerta de que solo se recicla en torno al 9% de todo el plástico que se ha producido en el mundo. Ante la incapacidad de dar una segunda vida a este material, que en muchas ocasiones es de usar y tirar, crear alternativas biodegradables y totalmente respetuosas con el medio ambiente es un desafío urgente.

· — —

Tungsteno es un laboratorio periodístico que explora la esencia de la innovación. Ideado por Materia Publicaciones Científicas para el blog de Sacyr.