Industrialization brings factory-style processes into the construction sector, enhancing productivity and introducing a high degree of automation. It encompasses research and innovation in mechanizing and assembling components in a factory setting, applying these techniques to prefabricate various elements like bathrooms, facades, and technical partitions.

This approach is faster and more sustainable, minimizing waste and requiring fewer energy resources, while also simplifying maintenance.

Bathrooms and facades are among the first elements to undergo this industrialization, according to Mónica Silva Laiz, Head of Building at Sacyr Engineering and Infrastructure Engineering department in Spain.

"Industrialised construction is here to stay, and we are today one of the pioneering companies in carrying out this transformation. It is a new way of conceiving construction," explains Mónica Silva.

Sacyr is implementing industrialization as a key component in projects across Chile, the United Kingdom, Spain, and Italy.

In Chile, we operate a factory assembling prefabricated bathrooms for three hospitals: Sótero del Río, Cordillera, and Buine Paine.

The construction of the Milan Hospital in Italy also incorporates industrialized bathrooms and facade sections.

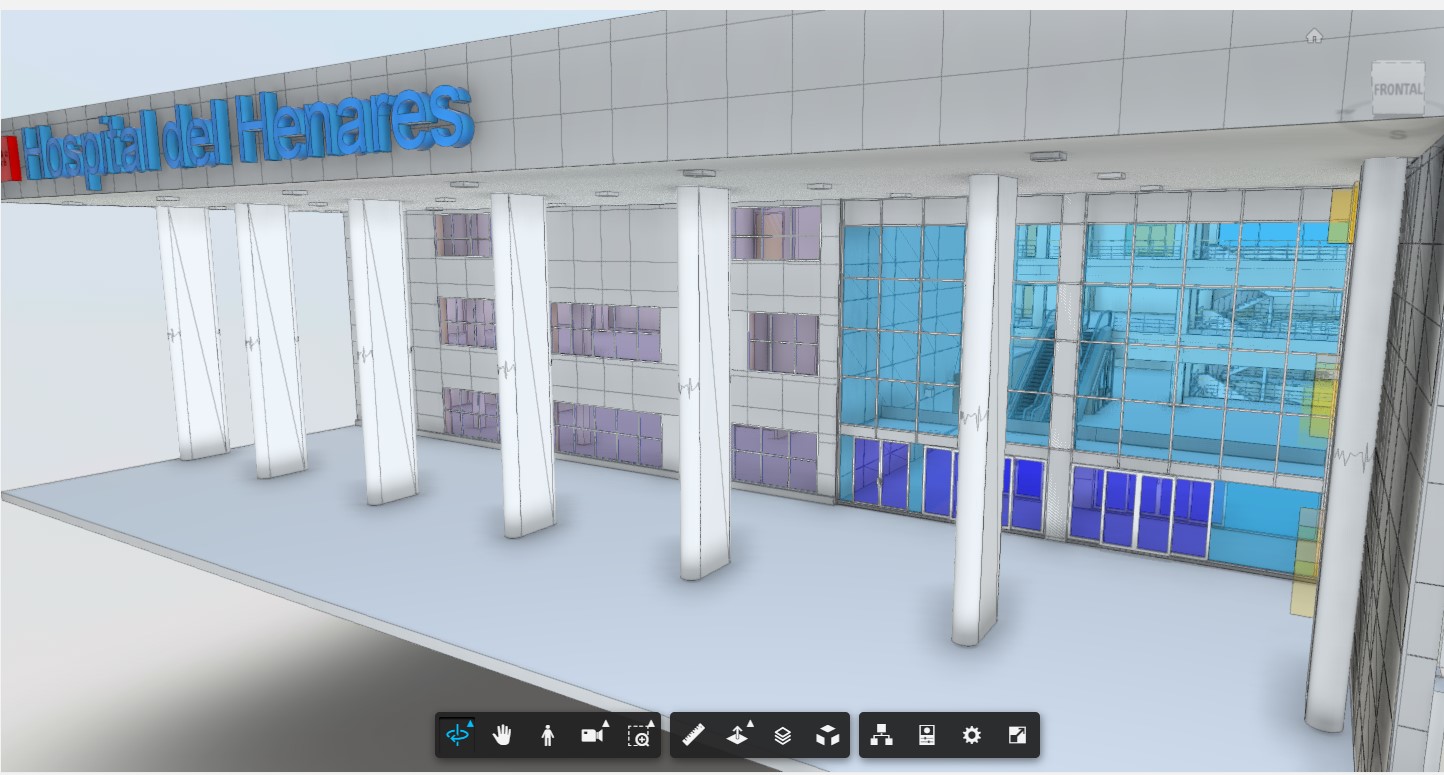

In Spain, we've employed these factory processes at the 12 de Octubre Hospital, installing prefabricated GRC (glass fiber reinforced concrete on a metal frame) facades, among other elements. These methods are also being implemented in residential developments across several Spanish regions.

At the New Velindre Cancer Center in Cardiff (Wales, UK), we're constructing prefabricated facades using light steel frames with external finishes in wood and copper sheets, incorporating windows and glazing. The facade modules are manufactured in Spain and shipped to the UK for on-site assembly.

Furthermore, through the Valdesc project, we're exploring a novel industrialized construction system for facade envelopes using recycled materials, ensuring high rates of circularity and decarbonization. This system will enhance thermal efficiency and simplify component dismantling, combining efficiency, productivity, and safety.